bring our railway into public ownership

The history

Our railway was privatised from 1994-1997, following the passing of The Railways Bill in 1993. Margaret Thatcher herself didn’t want to privatise British Rail, but her successor John Major decided to go ahead.

On 18th July 2024, the Labour government tabled the Passenger Railway Services (Public Ownership) Bill to bring all of Britain's railway lines into public ownership when their current private contracts expire. The bill does not include ownership of rolling stock.

Who currently owns our railway?

The rail network was carved up and today private train operating companies run 17 franchises across our railway. For a set number of years, they’re responsible for running train services covering a certain area, according to a specification set by the government.

There are lots of different companies running trains on our network in the UK. Ironically, many of them are actually state owned companies from other countries which operate as private sector companies here and return a profit back home. For example, Arriva is owned by the German government’s national railway company, Deutsche Bahn,and Abellio is owned by the Dutch state.

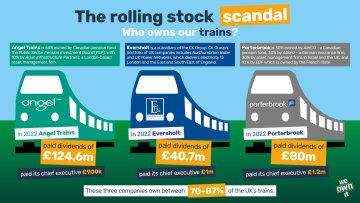

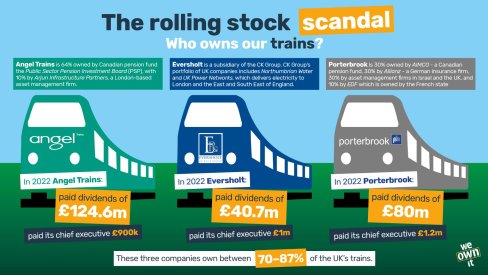

Three ROSCOs (Rolling Stock Companies) own and lease the trains themselves. Network Rail (which is publicly owned) manages the track and some of the stations.

The infrastructure itself was originally put under control of privatised ‘Railtrack’ – but after fatal accidents, publicly owned Network Rail took over in 2002.

The railway is partly funded by the fares we pay, and partly by the government. Some rail fares are regulated by the government (like season tickets and off peak fares) and some are not (like advance and walk on fares).

Check out who owns some of the key rail companies here.

Key facts

- 76% of us, according to a YouGov poll from June 2024, think the railway should be in public ownership, including a majority of Conservative voters.

- Rail is a natural monopoly. When you’re standing on a railway platform waiting for the train, you don’t have a choice about which company to choose - there is no ‘market’.

- The UK has the highest fares in Europe, which makes it hard for people to take the train.

- Public ownership of the railway would save around £1.5 billion a year - that money could reduce fares by 18% or pay for 100 miles of new railway track.

- Since the pandemic, the government is guaranteeing the income of private rail companies so the private sector isn’t taking any risk.

- Public ownership isn’t a silver bullet. Our railways also need proper funding. Investment is crucial and pays for itself.

- Privatisation is failing and rail franchises are coming back into public ownership - Wales, Scotland and the East Coast, Southeastern, Northern franchises - why not just bring the whole network into public ownership?

- Switzerland has the best railway in Europe, and it’s in public ownership.

FAQs

Why is the railway important?

The railway is important for the economy, society and the environment. Rail is good for the economy - for every £1 of activity spent on rail, a further £2.50 of income is generated elsewhere in the economy. 1 in 5 households don’t have a car so they rely on public transport to get to work or leisure activities.

And tackling the climate crisis means making public transport easy for people so they can leave cars and planes behind. If you’re travelling from Glasgow to London, rail is the green option, producing around 18% of the carbon emissions of a plane journey and around 32% of the emissions of a car journey.

Are rail fares expensive in the UK?

Yes! Overall rail fares are up by at least 20% in real terms since privatisation. Some rail fares have even risen twice as fast as inflation. For example, in 1995 the price of a peak-time single ticket from London Paddington to Bristol was £28.50 - now it’s £115. Analysis by Barry Doe shows that some fares have risen by over 300% since privatisation.

Between 2009 and 2019, rail fares increased at twice the speed of wages, TUC analysis shows. In 2022, fares in England and Wales rose by 3.8%: their biggest increase in nine years.

Rail fares are also horrendously complicated - although the industry says it is working on making the system simpler, there are currently 55 million different fares!

Rail companies say that fares here compare well to elsewhere in Europe - what’s the truth?

While you can buy cheap advance tickets, walk on fares are incredibly high and so are season tickets.

The TUC has found that UK commuters spend up to five times as much on season tickets compared to other European passengers.

Fares expert Barry Doe, writing in RAIL magazine, names Avanti West Coast, East Midlands Railway and Great Western Railway inter-city as the operations that “outstrip all others for peak fares”.

Why are UK rail fares so expensive?

There are three main factors - inadequate government funding, inefficient fragmentation and shareholder profits leaking out of the system.

Privatisation is a key reason why fares are so high. This causes two problems:

- Our railway is hugely fragmented. The railway needs a ‘guiding mind’ and clear management structure. Privatisation has made it complicated: there are many different actors and no one knows who is in charge. Accountants, lawyers and consultants are involved at every stage. This is very inefficient. The McNulty report of 2011 found that railway costs in the UK are about 30% higher than elsewhere.

- Privatisation also means we waste money on shareholder dividends - that’s money that could be reinvested back into the system.

Alongside a fragmented, privatised railway, lack of government funding is another important reason why fares are so high. The railway is partly funded by fares and partly by government. The UK is uniquely obsessed with loading the cost onto passengers, with the government forcing passengers to pay more so it can pay less, whereas continental European countries understand the benefit of higher public funding. Our government is being short-sighted by cutting funding - as mentioned above, investing in the railway boosts the economy overall. It pays for itself!

Do shareholders really make much money from the railway?

The Train Operating Companies themselves get a relatively low rate of return in terms of the profit they make. In 2019-20 they made £262 million in dividends and £38 million last year. However, there are a few points to bear in mind:

- These millions are still a huge amount of money in absolute terms, and it’s currently being wasted. We could use this money to make rail travel more affordable, to open new stations or run better services.

- It makes no sense that publicly owned train companies from other countries run our trains and return the profit back to their own rail networks. For example, Arriva is owned by Deutsche Bahn in Germany and Abellio is owned by the Dutch.

- The Train Operating Companies also benefit from indirect subsidies from Network Rail. Public subsidy channelled through Network Rail has led to artificially low track access charges for train companies. In other words, the private companies running the trains are actually being propped up by the state.

- With privatisation, again and again, the government takes the risk when things go wrong while the private sector walks away with the profit. When train companies get their predictions wrong, as Richard Branson’s Virgin did on the East Coast line, they walk away instead of delivering the results they promised. During the pandemic, the government stepped in to protect train companies. If the private sector won’t take any risk, what’s the point of having them involved at all?

- It’s also important to notice that the three rolling stock companies (or ROSCOs) which own and lease the trains do make HUGE profits. RMT research shows that Angel, Eversholt and Porterbrook paid out nearly £1 billion in dividends at taxpayers’ expense 2020-21, the equivalent of half the £2 billion in fares paid by passengers and or 23% of the £8 billion in taxpayer support to the industry in the same year. Most of the dividends disappeared overseas into opaque companies based in Luxembourg and Jersey.

How would public ownership of the railway help passengers?

Overall, we waste around £1.5 billion a year on privatisation. If that money was put towards rail fares, we could cut them by 18%, or we could build 100 miles of new railway track.

In addition, we could plan for a railway fit for the future. A more efficient, well planned, publicly owned railway will help people leave cars and planes behind and help tackle the climate crisis. As Jonathan Tyler points out, public ownership would make it easier to coordinate a public transport timetable across the whole network.

Which rail franchises are already run in public ownership in the UK?

The ‘Operator of Last Resort’ is run by the Department for Transport, and takes over railway franchises when train operating companies fail to run services. This provides a fall back option for when privatisation goes wrong. Wales and Scotland have the devolved powers to run their railway directly, and both countries have now chosen to do this.

- In June 2018, the East Coast line run by London North Eastern Railway (LNER) was brought into public ownership after Virgin and Stagecoach failed to make the profits they were expecting and opted out.

- In March 2020, Northern Rail was brought into public ownership after years of unacceptable delays and cancellations under Arriva’s management.

- In February 2021, the Welsh Government took over Transport for Wales Rail, after KeolisAmey Wales collapsed as a result of the Covid pandemic.

- In October 2021, Southeastern was brought into public ownership after Govia attempted to defraud the taxpayer.

- In April 2022, Transport Scotland took over the ScotRail franchise following years of delays and cancellations by Abellio.

- In May 2023, Transpennine Express was taken into public ownership after systematic failures by the private operators of the franchise.

What about British Rail? Do you want to take us back to the 1970s?

We want to go forward to the future, not back to the past! That being said, it’s important to set the record straight. Supporters of privatisation like to criticise British Rail, but it was actually very efficient by the time it was privatised. In 1989, British Rail was recorded as being 40% more efficient than eight comparable rail systems in Europe used as benchmarks.

The truth is that British Rail was also hugely underfunded. Since privatisation, the government is spending around three times more on the railway. We need BOTH public ownership AND proper funding to have a railway fit for the future.

Christian Wolmar points out that in other countries like France and Germany, government owns the railway but it is managed by professionals who are given the freedom they need to attract passengers.

It doesn’t make sense to pretend our railway can be run like a market when it’s a natural monopoly. But under public ownership, we will still need mechanisms to make sure it’s delivering. In our report ‘When We Own It’, we make the case that passengers need a voice to hold railway managers accountable and keep pushing for services to be as high quality as possible. We suggest a governance model that gives passengers a say alongside professional managers and rail workers.

Passenger numbers have increased since privatisation - doesn’t that mean it was a success?

Passenger numbers have increased despite privatisation, not because of it. There are demographic and economic factors driving this.

Especially before the pandemic, many people had to commute into London, Birmingham, Glasgow and other metropolitan hubs. People often have limited transport options, meaning they don’t have much choice but to pay the high fares. But public ownership could make the railway a real choice for many more people and help us move away from cars and planes. Since the pandemic, working patterns are changing and leisure travel is becoming more important in relative terms.

Rail has also improved in some ways because - the government spends far more than in British Rail days (see our ‘What about British Rail’ section above).

What happened to the railway in the pandemic?

Passenger numbers fell off a cliff to levels not seen since 1872. In 2019-20, 1.7 billion journeys were made. In 2020-21, numbers dropped to 22% of this total (just 388 million journeys). The government spent over £10 billion propping up the industry.

The government should have brought all rail franchises in house to create a publicly owned network. Instead, it bailed out train operators and is now cutting funding by 10%. This isn’t the long term strategy and vision for our railway that we need. ‘Great British Railways’ is the same old system rebranded.

What about Japan? They have a good railway and it’s privatised

That’s true. Japan is a unique example. Unlike in other countries, most railways in Japan are financially independent and make a profit, rather than having to be subsidised. Its geography means that the rail network is dense and people have to rely on public transport. Punctuality is ingrained in Japanese culture. Japan has six separate geographical vertically integrated railways. Crucially, rail companies actually own the land around the railway and have diversified beyond just providing rail travel. They are in charge of housing and industrial development, shopping centres, hotel management, tourism and other modes of transport. For example, in JR East, one of Japan’s six railway divisions, more than 47% of its revenue came from non-rail related activities such as hotels. In any case, we would argue that the railway is an essential public service and public ownership is the best way to make sure it’s working well for everyone.

Which country should we copy?

Switzerland has the best railway in Europe. Swiss Federal Railways is a publicly owned rail network which is planned as part of a comprehensive, integrated public transport system where every village can rely on inter-connected, high quality services. The railway was ranked first among national European systems in the 2017 European Railway Performance Index for its intensity of use, quality of service, and safety rating.

How would you bring the railway into public ownership?

We can take rail franchises in house one at a time as they come up for renewal without paying a penny in compensation to shareholders. Five franchises have already been brought into public hands. Eventually we would be able to own and run the whole railway, plan for passengers across the entire network, and create a more efficient system like the Swiss railway. We already own the infrastructure through Network Rail. When new trains are needed, we can buy them directly on behalf of the public, and save ourselves the money currently going to rolling stock shareholders.

Has rail improved when franchises have come in house?

Often rail franchises have improved when they are brought into public ownership. For example, between 2009 and 2015 the East Coast line was run in public ownership after National Express walked out on the contract. In public ownership, the franchise was rated the most efficient in the UK - it required less public subsidy than before and was able to pay back £1 billion to the Treasury. It also achieved a customer satisfaction rate of 94%. Since the pandemic, publicly owned LNER has invested millions to improve services for passengers in innovative ways.

However, there are a few reasons why bringing isolated franchises into public hands might not always lead directly to an improvement in services:

- We need to bring the whole railway into public ownership to reap the benefits of an efficient, integrated network. While a handful of publicly owned franchises is better than none, most of the railway is still run by private companies in a patchwork, piecemeal way. We need to have one railway, with clear management, vision and planning across the network.

- We also need the railway to be well funded to deliver quality services. Right now the government is cutting funding to our railway which will damage it even if it is in public hands.

- Public ownership needs to be part of a vision for our railway for the future. The government needs to have a plan to shift people from cars and planes to public transport to tackle climate crisis.

- We need to take the opportunity to use public ownership as a way to give passengers more of a say, and create mechanisms for them to hold railway managers accountable for improving the service over time.

How would you make sure that the government doesn’t starve a publicly owned railway of cash?

Investment is vital. Public ownership makes sense because it’s more efficient but it’s crucial to have a government that understands the value of the railway and invests the way that other countries on the continent do. We need to make the case for ongoing investment in public transport and show that this is a popular and sensible policy.

For public services like rail which have some revenue, but not enough to cover the cost of providing the service to everyone, their funding will have to be supplemented by the Treasury. There are two ways to deal with this.

Firstly, we can have legislation that recognises the need for long term funding from government. Railway privatisation legislation put an obligation on the Transport Secretary to provide the private railway with a multi-year funding settlement. Even though it doesn’t say anything about how large the settlement should be, this has given the privatised railway financial security. British Rail never benefited from such settlements. Similar guarantees could and should be put in place as part of legislation for the future publicly owned network.

Secondly, more generally, we must fund public services properly. Public ownership is not a panacea and public services will not work well without adequate funding, whoever owns and runs them. Austerity has created terrible conditions for our public services.

The UK’s public spending is about 41% of our GDP – much lower than the average for similar European countries, which is nearly 49%. We rely on public services to have a good quality of life; they are the backbone of societies across the world. It’s time to recognise the short and long term value of investing in them.